Dionysian Anarchism

Egoist, communist anarchism. Philosophical, (anti-)political quotes, memes, my original writings etc. @AntiworkQuotes

نمایش بیشتر348

مشترکین

-124 ساعت

+27 روز

+1030 روز

- مشترکین

- پوشش پست

- ER - نسبت تعامل

در حال بارگیری داده...

معدل نمو المشتركين

در حال بارگیری داده...

Repost from N/a

Follow Begumpura on Instagram:

https://www.instagram.com/begumpura.antifa

Facebook page:

https://www.facebook.com/begumpura.antifa

WhatsApp channel link: https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaUYZFyL7UVZcYbBWI1n

Repost from Anti-work quotes

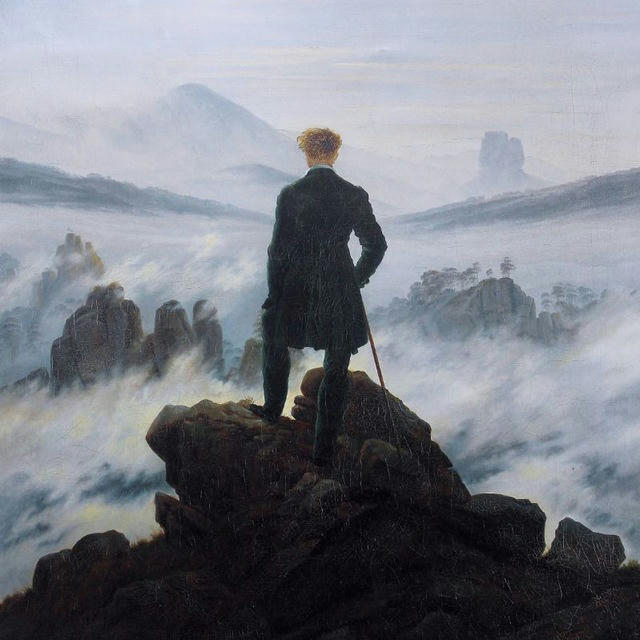

What is this life if, full of care, We have no time to stand and stare?— No time to stand beneath the boughs, And stare as long as sheep and cows: No time to see, when woods we pass, Where squirrels hide their nuts in grass: No time to see, in broad daylight, Streams full of stars, like skies at night: No time to turn at Beauty's glance, And watch her feet, how they can dance: No time to wait till her mouth can Enrich that smile her eyes began? A poor life this if, full of care, We have no time to stand and stare.— William H. Davies, Leisure

I became alive once more. At the dances I was one of the most untiring and gayest. One evening a cousin of Sasha, a young boy, took me aside. With a grave face, as if he were about to announce the death of a dear comrade, he whispered to me that it did not behoove an agitator to dance. Certainly not with such reckless abandon, anyway. It was undignified for one who was on the way to become a force in the anarchist movement. My frivolity would only hurt the Cause. I grew furious at the impudent interference of the boy. I told him to mind his own business, I was tired of having the Cause constantly thrown into my face. I did not believe that a Cause which stood for a beautiful ideal, for anarchism, for release and freedom from conventions and prejudice, should demand the denial of life and joy. I insisted that our Cause could not expect me to become a nun and that the movement should not be turned into a cloister. If it meant that, I did not want it. ‘I want freedom, the right to self-expression, everybody’s right to beautiful, radiant things.’ Anarchism meant that to me, and I would live it in spite of the whole world – prisons, persecution, everything. Yes, even in spite of the condemnation of my own closest comrades I would live my beautiful ideal.— Emma Goldman, Living My Life

❤ 1🔥 1

Punishment follows crime. If crime falls because the sacred disappears, punishment must no less be dragged into its fall; because it too only has meaning in relation to something sacred. They have abolished ecclesiastical punishments. Why? Because how someone behaves toward the “holy God” is his own affair. But as this one punishment, ecclesiastical punishment, has fallen, so all punishments must fall. As sin against the so-called God is a person's own affair, so is that against every sort of so-called sacred thing. According to our theories of penal law, with whose “timely improvement” people are struggling in vain, they want to punish people for this or that “inhumanity” and make the foolishness of these theories especially clear by their consequences, in that they hang the little thieves and let the big ones go. For violation of property, you have the penitentiary, while for “forced thought,” suppression of “natural human rights,” only—presentations and petitions. The criminal code has continued existence only through the sacred, and falls to pieces by itself if they give up punishment. Now everywhere they want to create a new penal law without having reservations about punishment. But it is precisely punishment that must give way to satisfaction, which again cannot aim at satisfying right or justice, but at procuring a satisfactory outcome for us. If one does to us something we won't put up with, we break his power and bring our own to bear; we satisfy ourselves on him and don't fall into the folly of trying to satisfy right (the phantasm). The sacred isn't to defend itself against human beings, but rather the human being is to defend himself against human beings; as, of course, God too no longer defends himself against human beings, that God to whom once and in part, indeed, even now, all “God's servants” offered their hands to punish the blasphemer, as still to this very day, they offer their hands to the sacred. That devotion to the sacred also brings it about that without any lively interest of one's own, one only delivers malefactors into the hands of the police and the courts: an apathetic giving over to the authorities, “who will, of course, best administer sacred things.” The people goes utterly nuts, sending the police against everything that seems immoral, or even only unseemly, to it; and this popular rage for the moral protects the police institution more than the mere government could possibly protect it. In crime the egoist has up to now asserted himself and mocked the sacred; the breaking with the sacred, or rather of the sacred, can become general. A revolution never returns, but an immense, reckless, shameless, conscienceless, proud—crime, doesn't it rumble in the distant thunder, and don't you see how the sky grows ominously silent and gloomy?— Max Stirner, The Unique and Its Property

The best state would clearly be the one which has the most loyal citizens, and the more the devoted sense of legality is lost, the more the state, this system of morality, this moral life itself, becomes diminished in force and quality. With the “good citizens,” the good state also degenerates and dissolves into anarchy and lawlessness. “Respect for the law!” The state as a whole is held together by this cement. “The law is sacred, and anyone who transgresses it is a criminal.” Without crime, no state: the moral world—and that is the state—is stuffed full of rogues, swindlers, liars, thieves, etc. Since the state is the rule of law, its hierarchy, therefore the egoist, in all cases where his advantage runs up against the state, can only satisfy himself through crime. The state cannot give up the claim that its laws and regulations are sacred. With this, the individual is considered precisely as the unholy (barbarian, natural human being, egoist), since he is against the state, which is precisely how the church once viewed him.

As the church had mortal sins, so the state has capital crimes; as the one had heretics, so the other has traitors; the one had ecclesiastical penalties, the other has criminal penalties; the one had inquisitorial trials, the other has fiscal trials; in short, there sins, here crimes, there sinners, here criminals, there inquisition and here—inquisition. Won't the sanctity of the state fall like that of the church? The awe of its laws, the reverence of its sovereignty, the humility of its “subjects”—will this last? Will the “sacred face” not be disfigured? What a folly to demand of state power that it should enter into an honest fight with the individual, and, as one expresses himself with freedom of the press, share sun and wind equally! If the state, this concept, is to be an effective power, it must simply be a higher power against the individual. The state is “sacred” and should not expose itself to the “impudent attacks” of individuals. If the state is sacred, then there must be censorship. The political liberals acknowledge the former and deny the consequence. But in any case, they concede repressive penalties to it, because—they insist that the state is more than the individual and practices a justified revenge, called punishment. Punishment only has a meaning when it is to grant atonement for the violation of a sacred thing.

Weitling lays the blame for crime on “social disorder” and lives in the expectation that under communist institutions crimes will become impossible because the temptations to them, such as money, will be removed. But since his organized society is also extolled as sacred and inviolable, he miscalculates in that kind-hearted opinion. Those who declared their support with their mouth for the communist society, but worked underhandedly for its ruin, would not be lacking. Besides, Weitling has to continue with “remedies against the natural remainder of human diseases and weaknesses,” and “remedies” always announce at the start that one considers individuals to be “called” to a certain “well-being” [Heil] and will consequently treat them in accordance with this “human calling.” The remedy or cure is only the reverse side of punishment, the theory of cure runs parallel with the theory of punishment; if the latter sees in an action a sin against right, the former takes it for a sin against himself, as a wasting of his health. But the appropriate thing is for me to look at it as an action that suits me or that doesn't suit me, as hostile or friendly to me, i.e., that I treat it as my property, which I cultivate or destroy. Neither “crime” nor “disease” is an egoist view of the matter, i.e., a judgment coming from me, but from something else, namely whether it violates the right, generally, or the health in part of the individual (the sick one) and in part of the universal (society). “Crime” is treated implacably, “disease” with “loving kindness, compassion,” and the like.— Max Stirner, The Unique and Its Property

یک طرح متفاوت انتخاب کنید

طرح فعلی شما تنها برای 5 کانال تجزیه و تحلیل را مجاز می کند. برای بیشتر، لطفا یک طرح دیگر انتخاب کنید.