Берлинские истории журнал покажет наш

1 482

Suscriptores

+124 horas

+77 días

-130 días

- Suscriptores

- Cobertura postal

- ER - ratio de compromiso

Carga de datos en curso...

Tasa de crecimiento de suscriptores

Carga de datos en curso...

Парочка новых кандидатов для моей премии «самый несовременный дизайн сайта».

Бонусные очки второму за то, что все ссылки сломаны 👌🏻

😁 1

P.S. Дождь и гроза свернулись в районе шести вечера, поэтому многие события вчера всё-таки состоялись, хотя все организаторы перенервничали.

Для меня большой плюс, что многие решили «фу, льёт, не пойду», поэтому почти не было толпы 😁

Также толпы почти не было, потому что параллельно шли футбольные матчи. Оказывается, в Ф-хайне куча ресторанов поставили огромные панели и все смотрят.

Даже в шпэти смотрят:

❤ 3

Примерно в день летнего солнцестояния — время самых длинных дней лета — проходит в Берлине пятничный хаотичный фестиваль музыки под открытым небом, названный почему-то на французском: https://www.fetedelamusique.de/

Выглядит в теории хорошо, а на практике надо разбираться. В прошлом году я выбрать, куда идти, не смогла, примкнуть было не к кому и я с досадой осталась дома.

На этот раз у меня есть подружка, посещающая его каждый год. Обещает всё показать на местности. Посмотрим. Также возможно посмотрим на грозу.

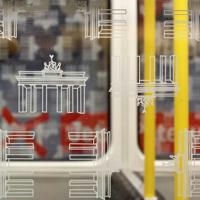

BVG (общественный транспорт) сварганил рилз в тему:

🔥 4

Elige un Plan Diferente

Tu plan actual sólo permite el análisis de 5 canales. Para obtener más, elige otro plan.